Integral Humanism Initiative

Integral Humanism Initiative By Centre for Human Sciences,

Overview

The present world order has seen the failures of many absolute economic and social models like aristocracy, authoritarianism, monarchy, socialism, communism, and capitalism. History tells us that these brief failed models arose out of religious, ethnic, cultural, and political conflicts. It is high time to understand Pt. Deen Daya Upadhayay’s thoughts and works that talk about the concept of “Integral Humanism”, which refers to looking at the world from a human-centric point of view. It envisions an organic unity and integrity between materiality and spirituality and views them as a collective entity. His thoughts on nationalism, economics, politics, and spirituality are all the more relevant in today’s times where greed, identity, and superiority seem to have become the motto of survival. Pt Deen Dayal gave importance to limited identity and discussed gradually moving towards an integrated global identity.

Unlike the Western concept, Indian thought doesn’t regard a man as a political or a social creature but as a universe in itself. It says “Aham Brahmasmi” (I am Brahma) and “Tat Twam Asi” (the same lies in everyone). Brahma refers to Samagrata and Sampoornta.

Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyay’s philosophy goes beyond the fixed compass of western thoughts. He can be called the first flag bearer of “Decolonisation” since he discussed the importance of the Sanskrit language, heritage, political activism, etc in society. His ideas on Rajneeti, Arthaneeti, Samaj, and Rashtra were well appreciated and were very well inculcated in the minds of his followers. For samaj shastra, he emphasized the important role of families in strengthening society. In Artha Neeti he gave the concept of ‘Antyodaya’ (a compound word made up of a combination of ‘ant’ and ‘uday’ referring to last and to rise respectively, and denoting the rise of the last person of the society). He also emphasized the importance of adopting swadeshi economic policies. He talks about the important role of the family as an institution in building up the nation. His idea of Dharma Rajya represents an ideal state having respect and equality of all faiths. The western concept of Rajya is rights oriented, whereas the Indian concept of Rajya is duty oriented.

Let us look at all the domains of Economics, Politics, Social, and Nationalism in detail:

Politics

The Indian political thought is beautifully explained in the Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva where Bheeshma Pitamaha gave the teaching of Raj Dharma which can be said as the first polis of Bharat. Indian political thought as described by the term Rajaneeti is not synonymous with the term, Politics. Rajneeti has three important aspects: Rajya (Polis), Rajya Tantra (Policy), and Raj Dharma (duty of ruler). It is because of this that autocracy never suited Indian political thought as the kings were bound by the concept of Dharma. Similarly, the natives were not called ‘citizens’ but ‘rashtraang’ meaning an integral part of Rashtra.

Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay talks about democracy without sanskaras. He believed that excessive democracy leads to anarchy. Democracy is just an instrument to fulfill a nation’s needs. He states that there is no conflict between individuals and society. The effectiveness of this instrument solely depends on the feeling of the people towards the nation, their consciousness of taking responsibility, and living a life with discipline. Unbridled liberty does not lead to the progress of an individual but to his ruin. The world can become happy with the concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam and never with sovereignty or markets.

Chitti and Rashtra Vs Nationalism

India believes in Bhu Sanskriti and Jan Judav, in contrast to the ideas of sovereignty and individualism of the West. The West believes that the souls of every individual are separate and individualistic, whereas the Indian thought says that one atma resides in all living creatures. When things are seen in discrete form, man (Vyakti), society (samaj), nation (rashtra), the world (Vishwa), nature (prakriti), nature (vanaspati), environment (vatavaran) – all are connected with each other.

The world today talks about Sustainable development, lest we understand that it is inherent in all the Indian thought heritage. From the very beginning, the Indian society has been functioning around the nature of what was available locally and based on self-reliance. Basic Indian living was based on the concept of a harmonious and inseparable relationship between human beings and nature.

The origin of the word “Nation” is in the word “native” which is essentially connected to the idea of race. In India, the word “nation” was translated as “jati” in the 1920s and 1930s by celebrated Indian poets like Sumitranandan Pant and Nirala. Badrishah Thulghariya in his book “Daishik Shastra” presents the quintessence of Bhartiya Civilization. He also uses the word “jati” for “nation”, the origin of which is from the word “janm”. So, the word ‘Rashtra’ does not have a similar word in English. Rashtra is not a nation. The word Rashtra is based on the concept of “Ekatva ” rather than birth or race. The form of Rashtra is seen in “chitt” (consciousness). The distinct expression of intelligence or awareness (chaitanya) is chitt (consciousness). It sees life as a journey from “limit to limitless”. The goal of Rashtra is the betterment of the world. It keeps the condition of one’s ultimate happiness, joy, sukha, ananda which can be attained only through serving others. ‘Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinaha’ highlights the importance of keeping others happy in order to attain one’s happiness. It emphasizes interconnectedness between all living beings as one soul resides in all. Hence, Indian thought never had the concept of “Individualism”. The word “Individual” comes from the Latin word “individuus” meaning, which cannot be further divided. It is wrongly translated in hindi as “vyakti”. “Vyakti ” comes from the word “vykta” which means “to express”. When a human being expresses what he sees is called “vyakti”. When “chitti” expresses itself it becomes the “vyaktitva” of that person. And this vyaktitva becomes the foundation of building a “rashtra” As Dr. Hegdewar says, “Rashtriya naturally meant ‘Hindu’ because it does not refer to a mere community living in India but to the reality that the land belongs to them. Even just one Hindu is enough to be called a “Rashtra”. So we understand that the idea of an individual is completely distinct in both cultures. From Rashtra, also comes ‘Rashtranga’ which is derived from the root word ‘rat’ meaning “that which shines” and having the same dreams, goals, and aspirations. Hence the idea of Rashtra is not divisive in nature. It is a wholesome idea that believes that the entire world needs to be happy for me to be happy. This expansive nature of Rashtra must be manifested in our economics, polity education, etc where Chitt is the soul of Rashtra which determines the rise and downfall of Rashtra.It is not a mere congregation and land, soil, and rocks.

Society

Panditji laid emphasis on nation-building through developing individuals, families, societies, and institutions through inculcating bhartiya values in education. He was of the view that education develops multi-dimensional personalities rooted in Indian ethos with strong character to lead societies, institutions, and nations. He also believed in the quality of teachers when he highlighted a hymn, “‘वयं राष्ट्रे जागृयाम पुरोहिताः” . He was of the opinion that education can inculcate values desired in the 21st century like sustainable development, self-dependence, individual freedom, social justice, culture preservation, etc.

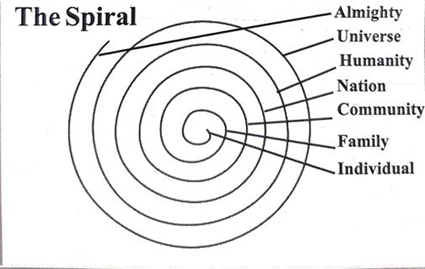

He laid utmost emphasis of the spiritual and moral development of an individual by following Dharma through 4 aggregate attributes i.e body, mind, heart, and intellect. He has explained the relationship between them through the following diagram which shows the growing levels of consciousness beginning from a single entity of “self” and expanding to the acceptance of the “universe” as its own, which shows that there are no conflicts between these entities and God can be attained once we accept the universe as part of our existence. It further says we are God-minded people hence we have intimate mutual relationships with all the entities of this universe, expounding on our very traditional thought of “dharma”. India very well demonstrated “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” during the global Covid pandemic which will take centuries to get fixed in the global thought heritage.

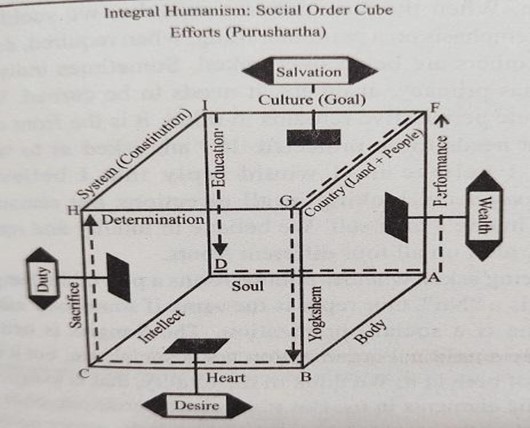

He explained the interrelationship between an individual, society, and nation with the help of a social order cube as follows:

The figure explains that society is the higher manifestation of an individual. ABCD represents the individual and FGHI represents society. There is a give and take between both.

- Education: It is the duty of a society to educate the last person in the society and make him capable to live life with dignity by earning a livelihood.

- Performance: An individual performs his duties based on the education provided by society

- Yogakshema (Remuneration): When a society reciprocates for all efforts put in by an individual and provides for better working conditions and payments.

- Sacrifice: This is something an individual saves for society. It can be money, effort, working for social causes, etc.

Economics

Deendayal ji’s works give a critique of Western philosophies that lead to the exploitation of natural resources, excessive consumerism for profits, capitalism, and socialism. He explains that a man should conduct himself in harmony with nature, whereas the west believes in individual supremacy over society and conquest of nature for its own benefits. The West believes in “survival of the fittest” whereas Bharatiya culture believes in protecting those who are weak because that is the only way a civilization can survive. The West gives utmost importance to struggle and conflicts and takes them to be the basis of society whereas Indian philosophy believes that all creatures are interdependent and complementary to each other and that there is no question of struggle. Their philosophies of capitalism and socialism are based on conflicts, struggle and atheism, and selfishness. The Indian values teach us to balance the use of labor, capital, and resources.

Antyodaya : Deen Dayal ji was a proponent of the idea of Antyodaya to bring those at the bottom of society to the top. His slogan “Har hath ko kaam har khet ko paani” laid utmost emphasis on agriculture and employment. He always believed agriculture to be our biggest strength but rather for several years we were trying to strengthen our weakness. It was not realized that a strong rural sector will raise demand for industrial products and it can happen only when the government works to raise the income of the people of the rural sector who have the maximum population residing there. Increasing their purchasing power should be the prime motive to boost the economy. Deendayalji believed that “Cow and Ox is the base of farming”.

Deen Dayal ji has also discussed ‘Ekatma Arthneeti’ where he talks about the balanced use of resources. According to Western philosophy, a man becomes addicted to acquiring wealth without any end and he always feels the dearth of material pleasures. Deen Dayal ji believed that ‘arth’ cannot solely be a motivator to a man. Both capitalism and socialism regard man as ‘economic man’ instead of ‘sampurna manav’. He is measured in quantitative terms and not qualitative.

Deendayal ji was also a firm believer in adopting the latest technologies and keeping up with the developments. But it is important to use technology rationally and not blindly follow the West. The technology used should be such that it leads to the development of humanism. Other than these, he has given utmost importance to decentralization, local production, private ownership, upskilling, etc.

Hence following are the objectives based on Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s unique ideology and its relevance in the modern era:

Aims and Objectives

- To compare and contrast this idea with other major theories such as capitalism, communism, and socialism

- To propose the implementation of his diverse ideas in practice

- To explore the similarities between Deen Dayal Ji’s Integral Humanism and Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy.

- To spread his ideas among the student community through seminars and symposia.

- To evaluate the efficacy of government policies under the name of Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyaya.

- To create awareness about Integral Humanism in academic, rural, and corporate circles.

- To imbibe his ideas to mold the younger generation through workshops, books, and classes.

- To examine his ideology from multi-disciplinary research activities

- To spread his ideas in rural and remote areas to local people.

- To acquaint the program with the teacher community.

- To develop a new generation of thinkers in line with Deen Dayal ji’s ideology

Research Methodology

Deen Dayal ji’s philosophy has a direct expansive impact on the process of benefitting the whole of society by bridging the gap between an individual to society, society to economics, spirituality to nation building. Hence, we have listed out three domains of setups where Upadhyaya’s ideology can be applied and the outcome can be measured. The three fields for understanding the application of Deen Dayal Upadhyay’s ideology are Academics, Social & Economics, and Corporates.

Academia: Deen Dayal Upadhyaya promoted the crux of the Indian idea of ethos i.e the realization of ‘Vyashti’, ‘Samashti’, ‘Srishti’, and ‘Parameshti’ and only education enables one to realize these illuminated values. In light of the New National Education Policy which focuses on holding back English values and promoting bhartiya values, it becomes rather more crucial for us to inculcate in students and teachers the love and understanding of amalgam of sanskar shiksha with formal education only through which the four Purusharthas as envisaged in Indian Philosophy can be attained.

Education prepares children and youth for serving society by modeling them as socially aware citizens. The gigantic task of nation-building lies on the shoulders of students and teachers who are said to be carriers of progress and welfare. They are also the conveyors of culture, cultural nationalism, and cultural values. The curriculum must be such that it anchors the holistic development of students and teachers into multi-dimensional personalities with strong characters by imbibing the values of the 21st century like self-dependence, self-control, sustainable development, cultural preservation, etc.

The research methodology in Academics will include visiting schools and other educational institutions and meeting and interacting with students and teachers through interviews and surveys. It will also include discussions and suggestions on improving the curriculum and evaluating the effectiveness of the current curriculum. Interacting with parents will also help in monitoring the performance and personality development of the students in line with their expectations. Various stakeholders like trustees and co-founders of school management and board will also be interacted with to know the vision and status of implementation of NEP. Various workshops, demonstrations, courses, books, and presentations will be made in schools for all teachers, students, and parents.

Other than these, we will also look for collaborations with various educational institutions to further and spread the thought works of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya ji through sponsorships, fellowships, conferences, symposiums, workshops, videos, courses, textbooks, etc.

Social and Economic: Deen Dayal Upadhyay envisioned development based on sustainability. He believed that the growth of India lies in the growth of agriculture, and it was crucial to becoming self-sufficient in food grains. He envisioned a strong rural development for Inclusive India built by local communities by employing adequate technologies to accelerate sustainable agricultural growth. He believed in decentralization and empowering local leaders and communities through proper training and skill and ability development.

The research shall involve visits to rural areas in various states and meeting various communities and local leaders to understand their development model and participatory processes and their efficacies. After careful study, workshops and training programs shall be held on organic farming, cow-based economy, women upliftment, recognizing small and marginal farmers and their problems, exploring and understanding their health and financial requirements, their rehabilitation needs, and introducing advanced farming techniques through innovation like the use of drones, etc.

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya ji advocated for a ‘guarantee of work for everyone. He also believed in the minimum wage security for all those who are unemployed or unable to work (sick, old, etc). He emphasized equitable distribution of wealth. For the development of India, he believed in the ideals of ‘decentralization’ and ‘swadeshi’. He regarded swadeshi as the cornerstone to restructure the Indian economy. Swadeshi not only means producing goods within the geographical barriers of India but also involves indigenous processes and patterns of development as a whole. He emphasized Indian individuality and specialty rather than being slaves to their processes and methods.

He regarded Agriculture as the backbone of industrial development. He believed in increasing the income of farmers and generating a marketable surplus for supply and exports which will in a way increase a farmer’s standard of living. He believed agriculture and industry must work in tandem and that they share a symbiotic relationship.

Following issues in Focus for Rural Development in view of Deen Dayal ji social and economic perspective and in the light of various Government initiatives and Programs:

● Landless and Marginal farmer Issues

● Suicide cases amongst farmers

● Health

● Financial security

● Innovation and Technology in Agriculture

● Exploring rural youth to other occupations like Forestry, Horticulture, Genetics, and plant breeding, Seed Science, Community science, soil science, Fisheries, Organic Farming, Agricultural Statistics, etc.

● Women Empowerment

● Education

● Migration issues

● Skill Development

● Promotion of local traditional talents in handicrafts, etc.

Corporate: When we talk about Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s focus on swadeshi and a self-reliant economy, we understand that the corporate world shares a big share of duty to strengthen the economy of India. Being cash rich with surplus capital and investments, labor, infrastructure, and government support, the companies are bound to society as their business solely depends on society. Society provides corporations with labor, land, and capital which must be diligently used for society and nation-building. In return, a corporation must provide society with goods and services, community welfare, employment, and equitable distribution of wealth.

The research methodology will include visiting renowned companies in specific sectors, medium to small-scale companies, cooperatives, sole proprietorships, and startups to understand their activities for community service and vision for a self-reliant nation. Various discussions on their idea of generating employment, training youth, their connection with academia, skill development of youth, indigenous production, Corporate social responsibility, etc will be conducted through surveys, interactions, workshops, and interviews.

Our major focus will be such companies that have proved themselves self-sufficient in that particular sector like sugar, jute, textiles, cotton, and garment market. The Atmanirbhar Bharat campaign has turned many sectors as global suppliers recently like food processing; organic farming; iron; aluminum and copper; agrochemicals; electronics; industrial machinery; furniture; leather and shoes; auto parts; textiles; and coveralls, masks, sanitizers, and ventilators. It will be interesting to know their stories on the following bullet points:

● Their success story and how-about of various steps taken in that direction

● Innovation and latest technologies employed

● Skill training of employees

● Placement of youth from academic institutes

● Indigenous processes exploited

● Contribution towards CSR

● Learning and Development of employees in the philosophy of Integral Humanism

● Company’s idea of Humanism and integral development of society

● Company’s contribution towards elevating human consciousness

● Spiritual and meditative practices in workplace

● Grooming workers as conscious citizens

● Studying their relationship with various stakeholders like investors, bankers, employees, community, third parties, blue collared workers, etc

Data Collection

Our research shall be both qualitative and quantitative based on primary and secondary sources.

- Primary sources:

- Internet Communication, Survey, Questionnaire

- Fieldwork and demonstrations

- Interviews and interactions

- Public Opinion Polls

- Government records

- Video recordings, Audio recordings, DVD’s

- Company/ Organisation documents

- Secondary Sources:

- Books and research papers on Deen Dayal Upadhyaya philosophy

- Reports of schemes by the name of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, its efficacy evaluation, deviations and monitoring

The Research Outcomes can be listed as below:

Academia

Courses/ books on:

● Samaaj shastra from Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s lens

● Arthaneeti from Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s lens

● Rashtra Neeti from Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s lens

● Rajya Neeti from Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s lens

● A small booklet on Antyodaya

● Western Nationalism vs Rashtriyata

● Deen Dayal Upadhyay : The Original Proponent of Decolonisation post Independent India

● Learnings from Deen Dayal’s Life

● Rajya, Raj Tantra, Raj Dharma

● Critique of Socialism and Communism from the point of view of DDU

● Akhand Bharat from the lens of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s philosophy

● A small booklet on his thoughts in quotation format to be distributed in schools.

Workshops / Conferences / Symposiums:

- Building values amongst students

- Sustainable Development is the core of Indian ethos

- Rajya, Raj Tantra, Raj Dharma

- Bhartiya perspective of Education for teachers in the light of National Education Policy and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s philosophy

- Relevance of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s thought in Decolonisation of Indian Minds

- Comparative Study on various political ideologies (Communism, Socialism, Marxism, etc)

- Workshop on Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s philosophy to rural and local leaders.

- The practices of Antodaya

Social and Economic

Workshops / Lectures:

- Society Building

- Collaborating with various community centres in rural areas

- Cultural activities

- Plantation and crop demos

- Libraries propagating the ideas of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya for youth to study

- Incorporating DDU ideology in curriculum of rural schools

- Adhyayan Kendra – platform for local leaders, youth and women to discuss on self reliance and development of village from the lens of DDU

- Exploring occupations with villagers to make them self reliant : solar lamps, SHG’s, digital literacy, horticulture, fisheries, poultry, water conservation etc and working on tangible benefits

- Educating teachers, parents and local leaders on the importance of integral humanism

- Collaborating with experts, government officials, academia, youth etc

- Connecting rural people with startups, academics by way of scholarships, internships, fellowships etc

Corporate

Workshops / Lectures /Collaborations:

● Presentations on DDU Philosophy of Integral Humanism in various departments of companies

● Training and workshops for employees inculcating in them universal thinking of integral humanism

● Guiding and connecting them with industry experts and academia regarding local production and employment, indegenious innovation and technologies etc

● Inculcating Deen Dayal Philosophy in the vision, mission and objectives on the company

● Training of youth and freshers to be conscious citizens executing the idea of integral humanism

● Circulating texts on the concepts of Antyodaya practices, swadeshi, swarajya, impetus to local production and employment

● Documenting brainstorming sessions on various issues like CSR, reskilling amd skilling, digital technology, innovation, value building of employees etc

Conclusion

The research project shall help to galvanise or ignite the spirit of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya universal philosophy in three sectors namely: Academics, Social and Economic, and Corporate. It will help to understand his ideas on Antyodaya, Universalism, traditionalism, cultural values, knowledge building, and spirituality in line with the Atma of Bharat Mata and make India a Vishwaguru.

Scope

Globally, the research will help in understanding India’s efforts to attain Sustainable Development Goals 2030 through Integral Humanism, Effectiveness of all government policies under the name of Pt. Deen Dayal Upadhyay, resolving global conflicts through Deen Dayal Upadhyaya’s philosophy like

- Global Vs Local

- Individualism Vs universalism

- Traditional vs Modernism

- Short term vs Long term

- Competition vs concern for equality

- Knowledge explosion vs Capacity to assimilate

- Spiritual vs Materialistic

It will also encourage future researchers to work on brief ideas of Deen Dayal Upadhyaya on education, employment, promotion of Sanskrit language, political activism, Akhand Bharat, etc.

Blogs

Revelation of the Roots and Essence of Antyodaya: A Journey Through Indian Philosophical Wisdom

Antyodaya, pioneered by Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay, isn’t just a new idea—it’s a revival of our ancient philosophies, tailored to meet the challenges of today. Its roots run deep in India’s traditional wisdom, reflecting a timeless ethos rather than a modern innovation. To grasp the essence of Antyodaya, we must journey back to its origins. Exploring...Read More