It is in the race for Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, that the world witnessed the last phase of the Great Game One.

By Dr Pankaj Saxena, Director for Centre for Cultural Studies

In 1893, with the final mapping and bridging of the Pamir Gap on one hand and the fixing of the Afghan-Russian Empire border on the other, most of central Asia was finally divided amongst three great powers. China had reclaimed Xinxiang, though very nominally, which it had earlier lost to the Islamic Jihad of Yakub Beg. With Afghanistan firmly in the British camp after the Second Afghan War and after the Durand Line had finally fixed its border with British India, the only independent player in Central Asia was the vast tract of land which was more mythical than real: Tibet.

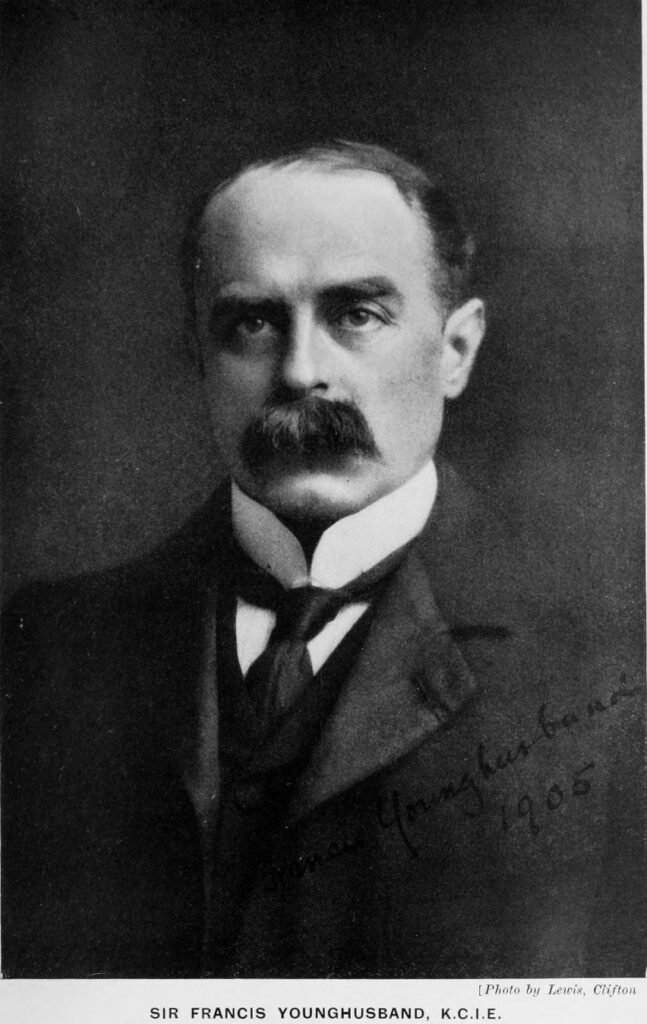

It is in the race for Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, that the world witnessed the last phase of the Great Game One. In a bid to occupy and influence the last bit of independent and mysterious kingdoms, as many as nine countries were in a rush to reach Lhasa. Before Francis Younghusband forced his way into Lhasa along with British troops no western power had set foot in Lhasa, the Forbidden City. Only stray missionaries and travelers had managed to get inside Tibet earlier but only secretly and much to their peril. And they had never reached Lhasa itself.

Tibet Denies Chinese Suzerainty

But the Great Game was heating up and the borderlands could no longer afford to remain independent. With the greatest of the central Asian khanates and cities occupied by Russia like Khiva, Samarkand, Bokhara, Merv, Tashkent, Khokand and others occupied by China and Britain, Tibet was the last independent kingdom left. Naturally, everyone’s attention was then attracted to Tibet. This is the story of the last phase of the Great Game One. As Hopkirk says:

“Tsarist armies were advancing – menacingly the British believed – across Central Asia towards India. It was feared for the safety of the latter which stirred strategists in London and Calcutta to look with sudden new interest at the kingdoms and khanates lying in the path of the Russian advance. Until then, apart from Afghanistan, these had counted for little. But now they acquired a crucial significance. And none more than the Buddhist kingdom of Tibet, the largest and least known of them all.” (Trespassers… 19)

In 1865, Tibet was a great white blank on most western maps. There was no knowledge of the precise locations of even Lhasa or Shigatse, the biggest towns of Tibet. Tibet had closed its gates off to foreigners, especially westerners. But the Great Game was heating up and the British officers in India already had eyes on Tibet.

The Tibetans had shut gates in the 19th century. A regular Nepali invasion in 1792 was interpreted by their Chinese friends as British intrigue. The Tibetans feared losing their religion most of all and thus they abhorred Christian missionaries. The exploits of the Hindu Pundits of British India had whetted the appetite to explore Tibet.

As a result, explorers from as many as nine countries rushed in the race towards Lhasa. One of the first was the Russian Colonel Nikolai Prejevalsky who came from the north and wanted to enter Lhasa in 1878. But Tibetans dispatched monks to the north who refused passage to Prejevalsky. When the Russian Colonel brandished his Chinese passport which the Russian government had procured for him, the Tibetan monks told him that the Chinese were only friends and the Tibetans did not take orders from them. The Russians had to go back and Tibet remained safe for a while.

The next party to attempt a passage was the British one. But they were also denied passage and the stalemate continued for some time. Before things went bad, the British struck a deal with China and in return for Chinese acceptance of British annexation of northern Burma, the British party would leave Tibetans alone.

However, the Tibetans fearing further invasions from Britain stationed an army of monks inside 18 kilometers of Sikkim which they considered their vassal state. They were not ready to accept any Sikkim-British accord. The army was visible from Darjeeling. The British were infuriated and tried to convince the Chinese to tell the Tibetans to back off, scarcely realizing that the Chinese governor in Tibet was merely respected in trade and other relations and China had no real control of Tibet.

In March 1888, Tibetans and the British army came to clash on Sikkim’s soil. The Tibetans had courage and determination but the only arms they had were matchlocks and swords and were no match for the British. The British lost only one man and the Tibetans lost two hundred. Though the British won this battle, the British reputation suffered a serious setback in the Tibetan capital.

International Players Enter the Race

The race for Lhasa had by then encouraged some lone explorers like the American William Woodville Rockhill. He came from China and thus had to cross the harsh deserts before he reached the Tibetan borders. But he simply could not proceed further and had to turn back in 1888. His dream of reaching Lhasa failed even in another attempt some years later.

Meanwhile, another individual, the Englishman and a Reverend, Henry Lansdell was also making attempt to reach Lhasa. He was actually funded by the Church of England and pretended to carry the Letter of Grand Lama of the West (Christian Church) to the Grand Lama of the East. But his ruse was not to be entertained and he also failed to enter Tibet. A Frenchman Gabriel Bonvalot tried to reach Lhasa from the North, crossing the formidable Altyn Tagh Mountains. But they were also intercepted by the Tibetans and sent back. The Tibetans were determined not to let any ‘whites’ enter their sacred land.

Two British men Hamilton Bower and H. G. Thorold attempted once again from the North and travelled very near Lhasa but were once again turned back by the Tibetans. However, they managed to gather some more information about Tibet’s northern passes.

Christian Missionaries Make their Move

By the 1890s Christian missionaries were making serious attempts at breaching Tibet and converting it. China which held a very fragile diplomatic sway over Tibet would regularly scare Tibetans by saying that the Russian and British were Christian missionaries who were out to destroy the ancient religion of Tibet and convert them to Christianity.

In this, the Chinese were of course right. The missionaries were indeed after Tibetan Buddhism and its ancient pagan religion. Annie Taylor, Jules de Rhins and George Littledale were some of the most persistent Christian missionaries who tried to get inside Tibet – to Lhasa.

Henry Savage Landor was an intrepid if spurious traveler to Tibet, who with the considerable help of his two Hindu aides, Chanden Singh and Man Singh got inside Tibet and traveled alongside Tsang-po but could not reach Lhasa. He along with his servants was severely punished by the Tibetans. When he returned to India alive, he wrote a bestseller on his experiences and his suffering was not forgotten by the British.

But all of these Christian missionaries and zealots were defeated and turned back. De Rhins died at the hands of the Tibetans. The Tibetans were resolute and punished by death even those Tibetans who brought foreigners inside Tibetan boundaries.

The Christian missionaries were very active in China in those times. In lieu of trade, the missionaries had deeply penetrated China. The two Boxer Wars and the Taiping Rebellions, some of the greatest wars of modern China all happened due to Christianity. The Tibetans knew that the weak Manchu Empire had been penetrated deep by the Christian missionaries and in 1887 they crossed their borders and destroyed a Christian mission inside the Chinese borders, killing all those inside, including the local Chinese converts.

One cannot blame the Tibetans for being so paranoid about the Christian missionaries entering their sacred city. The missionaries were zealous fanatics and thought so high of Christianity and so little of Tibetan religion that they were even ready for martyrdom in order to bring Christianity to Tibet. One of them Susie Rijnhart wrote that:

“If ever the gospel were proclaimed in Lhasa, someone would have to be the first to undertake the journey, to meet the difficulties, to preach the first sermon, and perhaps never return to tell the tale… The message of Christ, could not be taught without some suffering, some persecution, nay without tears and blood.” (Rijnhart) (Hopkirk 138)

The fanaticism of these Christian missionaries knew no bounds. Susie Rijnhart took her one year baby to Tibet, in the race to reach Lhasa. The high altitudes were too much for the lungs of the baby and he died on the dark and desolate plateaus of Tibet. After much suffering her husband was killed by the brigands and she was the only one who survived and reached her home in Canada. But she was so fanatically Christian that she married again and then with her second husband came once again to Tibet, in the race to reach Lhasa. But a few weeks after giving birth to another boy, she died.

Susie’s case has an uncanny resemblance to that Muslim woman of Shaheen Bagh who took her three months’ old baby to the racist, anti-Hindu and blatantly Islamic protests at Shaheen Bagh. Her baby died of exposure in Delhi winters. And yet she was unrepentant, saying that she could sacrifice even more of her babies for her religion. Susie Rijnhart was as fanatical in her faith in Christianity. Prophetic Monotheistic religions produce fanatics unheard of in pagan cultures.

Francis Younghusband Mounts the Invasion of Tibet

The British meanwhile were increasingly wary of the Russians in Central Asia. By the beginning of 1903, they were almost convinced that the Dalai Lama and the Russian Tsar had a secret deal and thus Tibet would also soon be gobbled up by the Russian Empire. Lord Curzon along with his friend, the already famous Great Game player Francis Younghusband was planning an invasion of Tibet. It was in principle just a friendly visit to ensure that the Russians were not already in Tibet, but on the ground it amounted to nothing less than an invasion. In 1903, the British had tried to negotiate with the Tibetans at Khamba Jong just three miles inside the Tibetan border, but the Tibetans did not agree.

As a result, another British force was sent into Tibet forcefully in the December of 1903. It was two thousand soldiers strong with modern weapons. But the contingent was more than 12,000 strong as around ten thousand coolies were needed to carry the armaments on the high Jelap Pass. The soldiers were the Sikh and Gurkha regiments. Maxim machine guns were also carried, which would be a game-changer in the engagement.

Tibetans on the other hand were armed with nothing but matchlocks and swords. But the British army passed over the Jelap Pass and then the walls of Yatun and finally over the great fortress of Phari too without any confrontation. The Tibetans kept protesting but did not put a fight. Just short of the village of Guru, the first bloody battle between the British and the Tibetans happened. This was the first engagement of the Tibetans with a European led army. The conclusion was foregone. More than seven hundred Tibetans were massacred in a matter of minutes in the grim March of 1904:

“In four terrible minutes, nearly seven hundred ragged and ill-armed Tibetans lay dead or dying on the plain. The Lhasa general was among the first to be killed. As volley after volley of rifle and machine-gun, a fire tore into their ranks from either flank and from across the wall, the survivors turned to flee. But instead of running, the Tibetans walked slowly off the battlefield with head best. It was a horrifying but moving sight, a medieval army disintegrating before the merciless fire-power of twentieth-century weapons. Even while his wounds were being dressed, Candler watched the rout. ‘They were bewildered’, he wrote, ‘The impossible had happened. Prayers and charms and mantras, and the holiest of their holy men, had failed them… They walked with bowed heads as if they had been disillusioned in their gods.’” (Hopkirk 175)

This was indeed unfortunate but it was a sign that armies had to be modernized and those modern geopolitics had to be understood in its global context otherwise on or the other foreign power would come to rule. This is a lesson which modern Indian leaders seemed to forget after independence and started believing in the hogwash of non-alignment and universal peace.

There were many engagements between the British and the Tibetans later. In the run-up to Gyantse the great fortress town of Tibet, two hundred Tibetans once again died with no casualty on the British side. It was once again a rout. At Karo Pass, approaching the great forbidden city of Lhasa, the British once again met a Tibetan force commanding great heights. A great and courageous battle was fought in which the British too left five men but the Tibetans lost more than four hundred. This Battle of the Karo Pass would become immortal in military history as it was fought at a greater altitude than any other in the history of warfare.

By now the British goal was to march to Lhasa itself and not just Gyantse. The Tibetans were resisting and so it was thought to teach them a lesson by stepping foot inside the sacred city. It was a belief in Tibet that if even one great fortress of theirs is occupied by a foreign force then it brings bad luck and then all would be lost. The Tibetans were losing heart in the battle. Very soon the British led Indian army commanded by Francis Younghusband entered Lhasa, the city which no foreigner had yet visited without getting discovered. Its golden roofs and domes were a sight which enthralled the British and the Indians.

The race to Lhasa was over.

China Excluded from the Anglo-Tibetan Convention

The British entered a treaty with Tibet called the Anglo-Tibetan Convention in September of 1904. This Convention guaranteed that the paths of Tibet would always be open to India. And that Tibet would not negotiate with any other foreign powers. The Indian Army under the British would keep occupying the Chumbi valley.

The treaty specifically excluded China from this agreement, whose ambassador was present in Lhasa at that time. This is significant as this fact makes the Anglo-Tibetan Convention basically a treaty between India and Tibet. Although in another treaty a couple of years later reverted back the situation to its former position in some respects, the sheer fact that the British thought of identifying, invading, and mapping Tibet and striking a treaty with them shows us how important they thought Tibet was going to be for India’s international security.

The Chinese tried to control Tibet after the British forces left but were bitterly fought and after three years of trench warfare they were hounded out of Tibet.The centuries-old Manchu dynasty fell in Beijing and the new Republican government tried to resume some form of contact with Tibet, an offer which the Dalai Lama declined pointedly. Any peripheral claim that China had on Tibet was now completely over. The British had meanwhile hosted the Dalai Lama in Darjeeling in India and in this way started a new relationship of the Dalai Lama with India and Indians.

The Tibetan Legacy for India

The British had behaved ignominiously towards Tibetans in their invasion; there is no doubt about that. They had defiled their holy city as no Christian had been allowed into the Forbidden City before. But they were doing so with a greater political purpose in their mind. Geopolitics is neither good nor bad. It is what it is. The British knew this and even though many of its officers had the air of white man’s burden on them, a lot of them knew that they were doing what was necessary to protect the borders of India.

The British did it for themselves, for the British Crown and for Christianity. But in any case, they left a glorious legacy for India to carry. Not only did they secure the western borders of India, but they also closed the Pamir Gap and insulated Indian borders from Russian territories. Then they secured the Sikkim-Tibet border. They went one step further and even though they knew that Tibet was claimed as a protectorate of China, they invaded and occupied Tibet at great cost so India could strike an independent treaty with Tibet. This was a legacy which if carried forward would have given India a free hand in Tibet. Had India protected Tibet by stationing its armies in Lhasa and at its borders, the geopolitical game today would have been completely different.

To think of this part of independent India’s history is painful to say the least. When the Red Army of communist China was invading Tibet, the Dalai Lama had appealed to India for help. But as the Dalai Lama records in his memoirs, he was bluntly refused by an arrogant and self-assured Nehru, who was head over heels in love with everything communist and was foolish enough to believe that the Chinese communists can do no wrong. The Dalai Lama says:

“The Indian Government also made it clear that they would not give us military help and advised us not to offer any armed resistance but to open negotiations for a peaceful settlement…” (The Dalai Lama 249)

To stress the monumental stupidity of Nehru, the British had once struck a treaty with Tibet to the benefit of India, excluding every other foreign power from Lhasa but allowing India. Then the Dalai Lama himself had asked for India’s military help. This was a golden moment to grab the opportunity and station India’s armies on the borders of Tibet, thereby gaining a perennial advantage over China, but Nehru’s monumental humbug did not let him see clearly.

Not only this, when the Red Army of China had occupied Tibet they were committing unspeakable atrocities on Tibetans and destroying Tibetan Buddhism which is much nearer to the Shakta sect in India. When the Tibetans tried to communicate to the wider world the atrocities committed upon them by contacting the Tibetan diaspora in India, the insolent Nehru tried every dirty trick in the book to block the Dalai Lama’s cries for help to the wider world. Here is what Peter Hopkirk says:

“Chinese attempts to crush to movement by means of harsh sentences, executions, deportations and other forms of reprisal were unsuccessful. But little of all this reached the outside world. Occasional rumors filtered through to India, but as these were impossible to check they were largely discounted in the West. It was Nehru’s policy at that time moreover, to placate his powerful Communist neighbor by discouraging such unfriendly stories. One British journalist living in Kalimpong was threatened with expulsion if he continued to write them.” (Hopkirk 253)

Even in 1958 much of Tibet south of the Tsang-po River was firmly in the control of the Tibetan rebels. India could have taken advantage of this situation and take control of at least half of Tibet and once again have the advantage of height and could have controlled the sacred headwaters of the Indus, the Brahmaputra and the Mekong. But they did no such thing for a communist stooge was controlling India at that time.

At first, south Tibet is where the Dalai Lama fled to after the Tibetan uprising against the Chinese. After the Dalai Lama fled Lhasa, the communist Chinese Army shelled the Potala Palace and massacred thousands upon thousands of Tibetans.

Expectedly the reaction of Nehru in India was nothing short of abominable. He tried to silence the Indian consul Ram Nath Kaul who was then stationed in Lhasa. It was from India that the communist atrocities on the Tibetans first came to light but the news was quickly suppressed by a communist stooge Nehru who seldom cared for peace or justice, and was more than ready to justify anything in support of communist China.

Very soon the Chinese would occupy Aksai Chin, which was Indian Territory and Nehru would not even realize that this had happened until much later. More important than this territory is the fact that China is now at India’s borders on all its northern and eastern borders. Making Pakistan and various central Asian countries its stooge, India is now surrounded from all sides by China. This ring would never have materialized if India had taken Tibet as a protectorate rather than China.

What the British had gained through great courage and immense hardships and great foresight in geopolitics, India lost spectacularly owing to its foolhardy policies under a communism-loving Nehru.

This article was first published at indiafacts.org.

References

- Dalai Lama. My Land and my People. Timeless Books, 2016.

- Hopkirk, Peter. Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Race for Lhasa. John Murray, 2006.

- Rijnhart, Susie. With the Tibetans in Tent and Temple. Forgotten Books, 2018.

- Younghusband, Francis. India and Tibet. Dover Publications, 2014.