Most of us relate slavery with an historical menace unleashed on millions of human beings in history and has no presence in contemprory world. But truth of the matter is that over 40 million people are victim of modern slavery, globally.

By Veerender Kumar, Research Associate, at Rashtram & Biplabjoy Purkayastha, Program Manager, Academic Operations at Rashtram

The 2013 American film 12 Years a Slave showed the story of Solomon Northup, an African-American violist, compelled into forced slavery for 12 years. The film vividly portrays the inhuman treatment meted out to him in those years, commenting on that time’s socio-economic condition. The film shows a happy ending for Northup, but the story hasn’t been the same for millions of people like him worldwide.

Fast forward post Second World War era, the global governance institutions took note of it and focused on eliminating this menace. As a part of this endeavour, the United Nations General Assembly approved the Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others on December 2, 1949. [1] This day is internationally recognised as the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery. [2]

However, the irony is that the world’s wealthiest country, the United States of America, which has witnessed fierce anti-slavery movements, including the civil war in its national history, has not ratified the above convention. [3] Even the Barack Obama Administration has not taken concrete steps.

USA is not the only defaulter here; countries like China, UK, Sweden, Germany, Turkey, etc., are the self-styled champions of liberty and human rights and belong to this list. This rakes up a crucial question on the relevance of this Convention and recognition of the Abolition of the Slavery Day itself.

The set of arguments presented by the defaulters include, inter alia,

- They have reservations regarding the referral of disputes arising due to violation of this Convention to ICJ.

- Many countries, including Germany, Netherlands, etc., permit voluntary prostitution, which conflicts with the provisions of the Convention.

- There are disagreements regarding the definition of trafficking. Many countries find the provisions of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime more acceptable than the so-called anti-slavery convention.

There is no doubt that these provisions have created more disagreements than consensus. Still, it is also true that USA and many others have not ratified many such global conventions. ILO website lists that so far USA has not ratified 66 Conventions and Protocols, many of which are fundamental in nature like: [4]

- C087 – Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87)

- C098 – Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining Convention, 1949 (No. 98)

- C100 – Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No. 100)

- C111 – Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111)

- C138 – Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138)

This shows that at the international level, the champions of human rights and liberty want others, especially countries like India, to comply with their worldview and standards while they themselves do not want to commit to such standards.

After understanding the dynamics of global governance around slavery, let us focus our attention on this issue’s global discourse.

In recent years, the global discourse on slavery is led by entities like the Walk Free Foundation, which publishes the Global Slavery Index, sometimes in partnership with ILO. [5] It provides a country by country ranking of the number of people in modern slavery, an analysis of the actions governments are taking to respond, and the factors that make people vulnerable. [6] Till 2016, its methodology was heavily criticised because of the lack of analytical rigour. In response, it has improved its methodology in recent years, but it is still under debate. Nonetheless, it has made some significant breakthroughs in shaping the discourse around slavery.

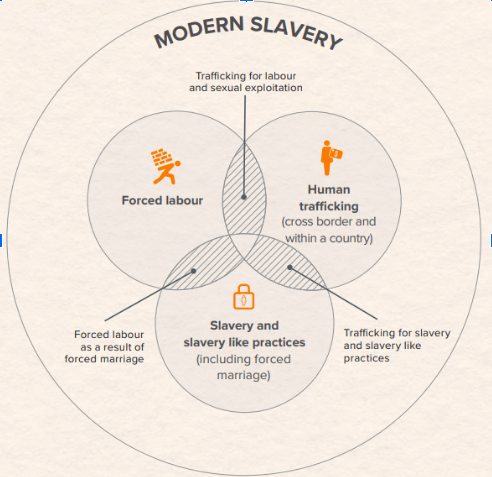

To begin with, the Global Slavery Index has defined slavery as follows: [7]

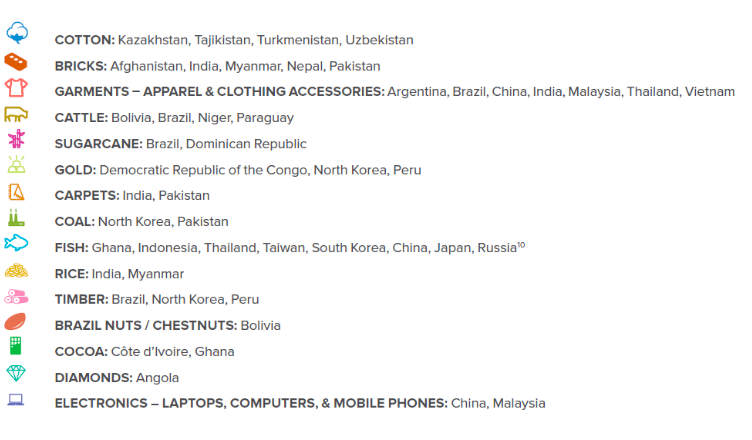

Taking this discussion forward, it has identified several products whose production process involves forced labour of any kind. Some of these products with their countries of concerns are as follows: [8]

The destinations of these products are worldwide; however, members of G20 are the most dominant importers, and US, UK, Canada, Germany, Japan, France, etc. top the list. [9]

These findings emerge that slavery has changed its form, and it has become an invisible part of the global supply chain. Therefore, those who consume specific types of products, which are at risk of slavery, are creating economic pull or incentives for so-called slavery.

This global network of economy, labour, and slavery is not new but an obvious product of European Colonization, racial supremacism, Arab supremacism, and Abrahamic supremacism. In many places, more than one of them combine to create so-called modern slavery. Kafala system of the Middle East is one such system that is an Arab and Islamic Supremacism product.

As per ILO, the Kafala (Sponsorship) System emerged in the 1950s to regulate the relationship between employers and migrant workers in many countries in West Asia. Under the Kafala system, a migrant worker’s immigration status is legally bound to an individual employer or sponsor (kafeel) for their contract period. The migrant worker cannot enter the country, transfer employment, nor leave the country for any reason without first obtaining explicit written permission from the kafeel. [10] These restrictions ultimately made migrant labourers bonded labourers, and their situation is not very different from slavery. In recent times, consistent efforts by different countries, including India, and changing dynamics of geopolitics in a post-oil era, have led to liberalizing the Kafala system and granting more rights to the migrant workers by the kafeels. Some of these efforts might get disrupted due to economic constraints brought by Covid-19, but some of these are also accelerated. So, a comprehensive picture will start emerging only after the subsidence of Covid-19.

Apart from conventions, colonization, a global supply chain of products and labour, and different forms of supremacisms, there is another dimension of discourse around slavery, predominant in India. This is the discourse around caste and arranged marriages (projected as forced marriages) as facilitators of slavery. This discourse is very much shaped by the superimposition of colonial categories of race on jati-varna and superimposition of the position of feminine identity and women in Abrahamic societies on the position of feminine identity and women in Indian society.

The Indian discourse on slavery requires a nuanced approach, and we will discuss it in a later blog post.

Concluding this brief article, we would like to emphasize that slavery in any form is condemnable, and it needs to be eradicated from the root. However, the question remains – whether we are having the right gaze and looking for shreds of evidence and commitment beyond our biases.

References

- Office of the Commissioner UN Human Rights https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/trafficinpersons.aspx

- Time and Date Website article on International Day for the Abolition of Slavery https://www.timeanddate.com/holidays/un/international-day-abolish-slavery

- UN Treaty Collection STATUS AS AT : 02-12-2020 03:15:49 EDT https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=VII-11-a&chapter=7&clang=_en

- ILO NORMLEX – Information System on International Labour Standards, Up-to-date Conventions and Protocols not ratified by United States of America https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11210:0::NO::P11210_COUNTRY_ID:102871

- https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/2018/methodology/prevalence/

- https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/about/the-index/

- The Global Slavery Index Report, The Walk Free Foundation, Page-7.

- Ibid. Page 103.

- Ibid. Page iv.

- ILO Migrant Forum in Asia Secretariat, Policy Brief No. 2: Reform of the Kafala (sponsorship) System https://www.ilo.org/dyn/migpractice/docs/132/PB2.pdf