Evolutionist and anthropological frameworks of interpretation have belittled the Vedic mantra as well as the Vedic Yajña by categorizing the two as naïve and obscure religious expressions (e.g. through labels like hymns and rituals, respectively) of the early humans. This article highlights the consciousness-altering potential of the Vedic Yajña and the role of the Vedic mantra in it by positing that the Vedic Yajña is neither just a ritual nor merely a metaphor; rather it is a powerful performative element in its own right, which pervades the ‘conditioned consciousness’ of its performer and uplifts the same to ever higher planes of consciousness, thus revealing to the performer/practitioner subtler layers of reality on the way to the Truth.

By Sreejit Datta, Assistant Professor, Director of Centre for Civilisational Studies & Resident Mentor

Self-consciousness, i.e. the state of awareness of one’s own self as a conscious entity, is barely present in the human child at the time of her birth. [1] It gradually develops in the human child as she grows up – she learns to recognize her body, she becomes conscious of her own emotions, she becomes aware of her weight, of the environment surrounding her, and the like, through the development of a sophisticated neural network.

New experiences, actions, and repeated actions i.e. practice give rise to newer neural connections in the child’s brain, making her self-consciousness richer by the day. By the time she attains teenage, she becomes aware of more complex feelings like sexuality; further advancement in age and experience makes her conscious of her cultural and political identity, thus transforming her into the sophisticated being that can be regarded as a complete human person.

An average human being, one who has attained complete personhood through her many interactions with the external world throughout the years of her maturation, would typically possess what we may call the conditioned consciousness. At this level of consciousness, the subject’s awareness remains confined to the awareness of her body, mind, and, at the most, her intellect.

Here, mind and intellect are being treated as two separate categories, wherein mind is the base that contains information (memory, feelings and thoughts) and intellect is the decision-making superstructure which is built on that foundation. Self-consciousness can rarely be found to have transcended the boundaries of the conditioned consciousness – even among those who are capable of making their way through the complexities and challenges of the human and the natural worlds.

Question arises: Are the boundaries of self-consciousness really going to be demarcated exclusively by the territories of body-mind-intellect, or are there other territories that could significantly expand the scope of self-consciousness? And if indeed there are such territories that transcend the body-mind-intellect, how can the individual access those areas?

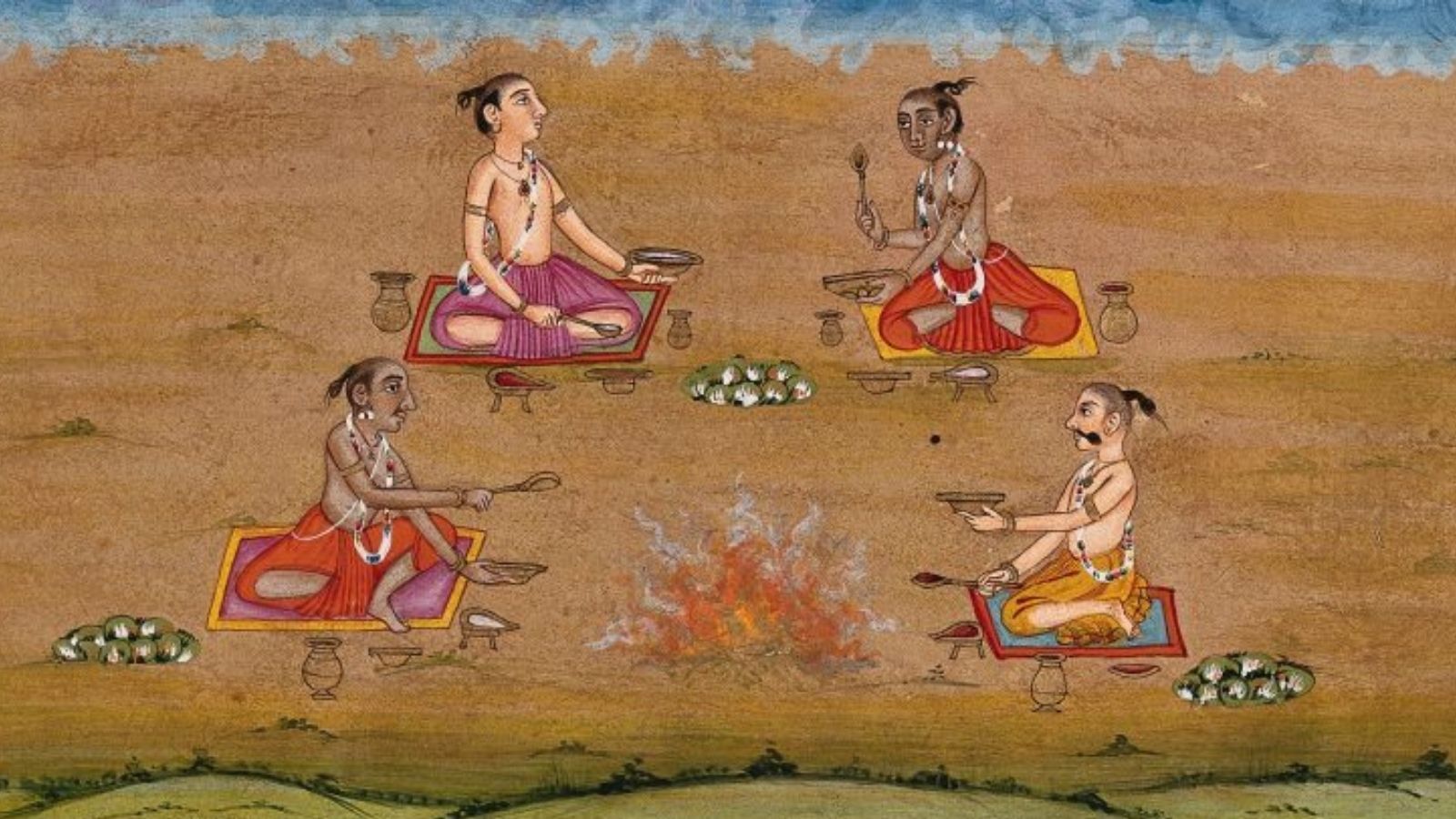

The fountainhead of all Indic Knowledge Systems, the Vedas, answer the first of these questions in the affirmative; and they also provide systematic methods to access the transcendental territories of consciousness, helping it break free of its conditionings. The key idea in this Vedic methodology is the Yajña – a tangible, performable idea that is meant to act as a conduit for transcending that state of consciousness which is conditioned by the habits of the body, the mind and the intellect, and therefore by their limited means of acquiring knowledge.

Over the last two centuries, the Vedic Yajña has been explained away by the Western evolutionists as a crude expression of the proto-religious activities of early humans. This view now pervades the scholarship in the field of Vedic studies in the premier universities of Europe and North America, and exercises considerable influence over the Indian academia, including a section of the Indian Sanskritists.

The situation is so bad that successive generations of students have been trained to regard the Vedic Yajña as little more than magic – as something equivalent to voodoo. This has caused immense damage to the general perception of and interpretative approaches to the Vedic Yajña. Fanciful English translations of the Vedic mantras have only perpetuated this pejorative understanding of the Vedic Yajña.

The Indic Civilization bears the legacy of two highly sophisticated and intellectually rich traditions, born out of varying degrees of emphasis laid on śraddhā, i.e. a respectful conviction on the efficacy of the Vedic mantras and tarka, i.e. logic. These two traditions are respectively known as the Rishi tradition and the Muni tradition. [2] Both attempt to have direct experience of Satya – The Truth – or, the ultimate substratum of reality, but by different methods.

The Rishi, relying on the Vedic Yajña, emphasizes more on the intuition and the force of the refined emotions; whereas the Muni stresses argumentation and rational thinking; and so his tool is chiefly intellectual, it is tarka. However, neither of them completely abhors the tools adopted by the other. Their goal is the same, viz. to give an upward thrust to the conditioned consciousness so that it can transcend its conditionings and perceive subtler layers of reality.

As such, the methodologies adopted and developed by those two traditions differ in character. We would designate these methodologies as sādhanā. But the Vedic Yajña does not remain a mere tool in the Rishi’s sādhanā. Through performance and practice, it seeps into all aspects of the practitioner’s life. It pervades her entire existence in the spheres of body, mind and intellect; and thus brings about a transformation in the individual.

This transformation is manifested as dharma–anuśāsana – the synchronizing of the individual human life with the universal life, a process which also includes establishing a near-perfect harmony between the rules governing the natural world and the life of the individual. The enlightened, realized Rishi thus lays down a value-system and leads an exemplary life for others to follow, not by enforcing them, but merely by existing: by being established in the pure consciousness which is also transcendental, beyond all conditionings.

This, in essence, is a translation of Satya into Ṛta. The mantra, which is the principal ingredient in the Yajña, plays a crucial role in this transformation as the conveyer of the vibes of this universal life, wherein everything is connected in a complex network of causality and interdependence.

The Vedic mantra is a spontaneous manifestation of the transcendental consciousness, which has been totally absorbed in the divine, completely immersed in the ‘Bliss Absolute’ [3] attainable only by the divinity-induced, singularly contemplative mind. Such a mind has already transcended the conditionings it has hitherto been subjected to; but the process also works when reversed.

That is to say, the mantra, when perfectly deployed, can provide the upward thrust which the conditioned consciousness requires to break free of its conditionings. The said perfect deployment of the mantra is achieved through a well-performed Vedic Yajña, whose principal objective is to deliver the conditioned self-consciousness to a transcendental plane of pure-consciousness by the sheer force of its meticulously engineered and highly emotionally charged dynamic actions. It is performance, but of a very sophisticated kind, one in which the performer and the props of the performance galvanize into a single vibration, attuned to a single frequency of consciousness-transforming force.

This article was first published in Indic Varta by the Centre for Indic Studies, Indus University.

References

- “When Does Consciousness Arise in Human Babies?” article by Christof Koch, published by Scientific American on September 1, 2009.

- Veda-Mimamsa (Vol. I) by Sri Anirvan, original Bengali text published under the auspices of the Government of West Bengal in the Calcutta Sanskrit College Research Series No. XIII, (Studies No. 4), Calcutta: 1961.

- Coinage introduced and popularized by Swami Vivekananda.