A lot of interesting debates dealing with multiple aspects of India’s society, spirituality, politics, economy and so on have been sparked off by people of various ideological affiliations.

By Sreejit Datta, Assistant Professor, Director of Civilisational Studies Practice & Resident Mentor at Rashtram.

This article was originally published on Indictoday.com

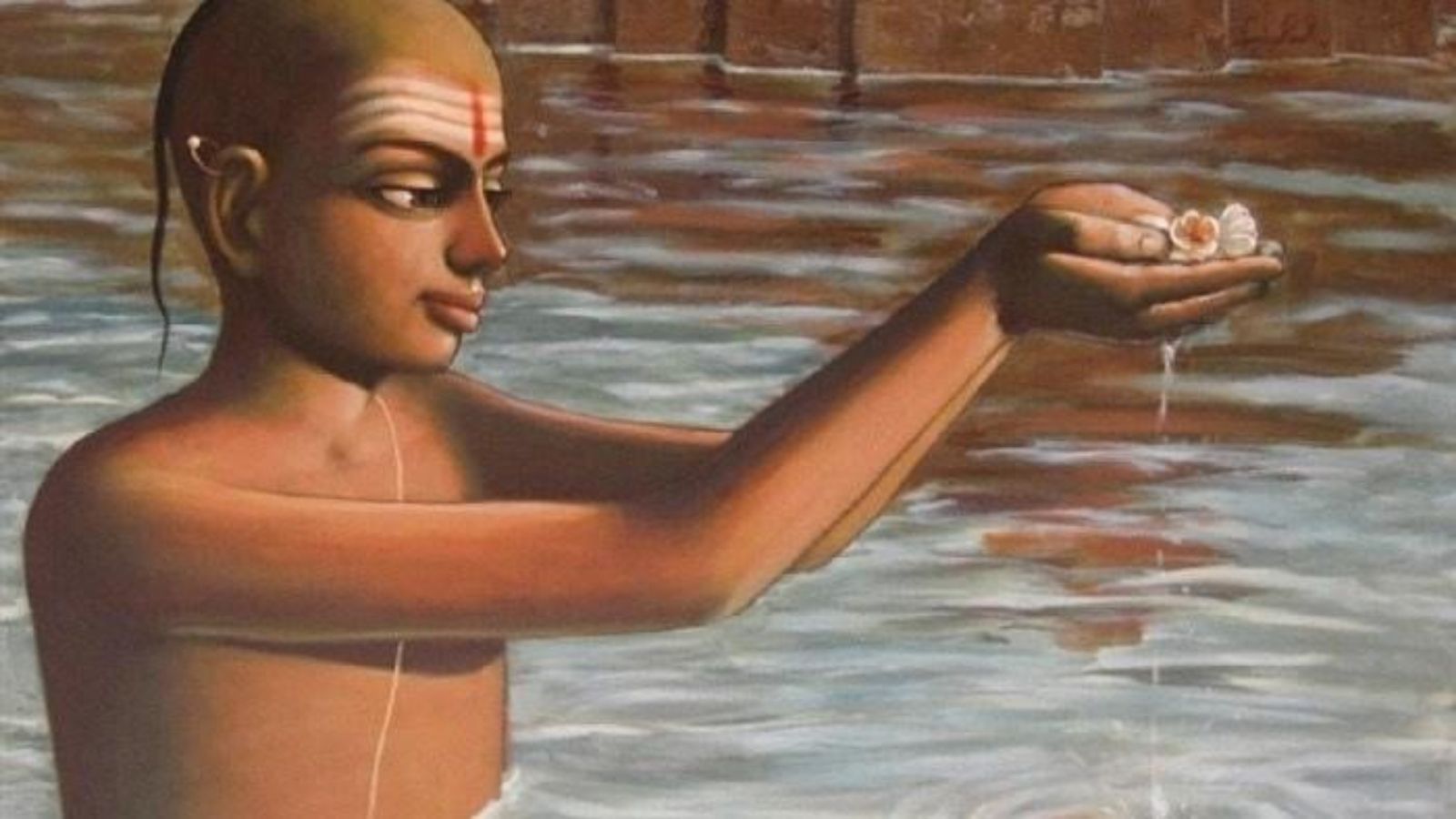

Image Source: Indictoday.com

Prologue to the Fourth Part

Since I started writing the present series on Hindu identity, a great many events of critical importance to the Hindu society and the Indic Civilisation have occurred on the Indian and global stage, and a lot of interesting debates dealing with multiple aspects of India’s society, spirituality, politics, economy and so on have been sparked off by people of various ideological affiliations.

Taking all these events and debates into account, I have felt the need to expand the scope of this series in terms of the depth of treatment administered to certain fundamental notions that are central to the present subject.

Therefore, unlike what was promised in the previous part, this series will not be concluded with the present part; and instead, it will continue with the addition of a few more parts to it wherein the notions of behavioral and interpersonal relationship, personal duty, and approaches to the Divine in the Hindu worldview will be discussed in some detail.

In the present and subsequent parts, however, we will take a close look at what is meant by ‘tradition’ in the Hindu, as well as the larger Indic context, since a lack of clarity regarding that concept among many has become evident through several of the recent events and current debates alike.

Āstikya Buddhi, or the ‘Hindu Tradition’

We frequently use the word ‘tradition’ in the discussions that revolve around terms such as ‘Sanātana Dharma’ or Hinduism, ‘Dharma’, ‘Dharmic’, and ‘Indic’. In the context of an old civilization such as ours, it is perhaps inevitable that one or more allusions and some rather direct references to tradition will be made in every discourse relating to our country’s history, politics, philosophy, culture, science, socioeconomic structure and so on.

But what does this word ‘tradition’ really mean in the context of the Indic Civilisation? We have also seen that, even in the most engaging contemporary discourses on India and Hinduism, the word ‘traditional’ is often used interchangeably with certain other terms like ‘Sanātana’, ‘Dharmic’, ‘Indic’ etc. – terms that have become a part of our day-to-day vocabulary in recent years.

Sometimes such usage is justified , especially when the speaker/writer has sufficient understanding of the tradition that they speak of or write about, understanding that is gained through their first-hand experience of living that very tradition, and not through mere reading or hearing from others — not even from their Guru.

Hearing and reading are no doubt important; in fact, together they form the first step to enter a life steeped in tradition and its attendant security and wisdom. Indeed, both the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad and its foremost teacher-commentator Bhagavatpāda Ādi Śaṁkarācārya have identified śravaṇa (hearing) as the starting point in the discovery of Self-Knowledge or the Supreme Secret, knowing which all is known. But merely reading or hearing about a tradition cannot take the place of actually living it.

Sadly enough, most of the esteemed participants of our enlightened contemporary discourses have little or no experience of living the tradition which they passionately defend or decry. It is not always a problem pertaining to the individual, but rather symptomatic of a larger problem gnawing at the roots of our society, mainly through the combination of a faulty education system and a damnably materialist approach to life.

Had it not been the case, there would have been a little less confusion as to the use (or abuse) of terms such as ‘Sanātana’, ‘Dharmic’, ‘Indic’, or, for that matter, the word ‘tradition’ itself; and as a result, our discourses would have been truly enlightening. These discourses are insubstantial at their best and misleading at their worst.

Most participants of these discourses skip the prerequisites of scientific methodology: that is to say, they directly indulge in the self-gratifying pleasures of interpreting a phenomenon, without bothering to experiment with it through active participation while carefully recording the observations or results of such an experiment is as dispassionate a manner as possible. Only then can the experimenter sit down to interpret the recorded data, not before.

In other words, most of our contemporary experts do not even qualify to participate in a meaningful and fruitful discussion touching upon the subject of tradition, let alone defend or refute it in any useful manner. The Sanskrit word to describe such experts is ‘anadhikāri’ — one who lacks the adhikāra to interpret any part of the tradition which they seek to defend or denounce. They are ineligible for such a serious service.

It is critically important to note that the word that Indians themselves have been using to denote the concept of ‘tradition’ is ‘Sanātana ’. This word, and its derivatives, have also come to denote concepts like ‘orthodox’ — e.g. it is not uncommon in India to come across someone referring to a person who strictly adheres to the more traditional ways of life as a ‘Sanātanī’, in contrast with other sects or paths who have reformed themselves to some extent. Sometimes the anglicized words ‘Sanatanist’ and ‘Sanatanism’ are used in this connection. Consider the following passages from Sri Sitaram Goel’s autobiography How I Became a Hindu for an illustration:

“The Arya Samaj of my young days in the village had three main themes to which they devoted the largest part of their programs: the Muslims, the Sanatanists, the Puranas. The Muslims were portrayed as people who could not help doing everything that was unwholesome. The Sanatanist Brahmins with their priestcraft were the great misleaders of mankind. And the Puranas, concocted by the Sanatanists, were the source of every superstition and puerile tradition prevalent in Hindu society.” (pp 4–5)

“But I did take very seriously the Arya Samajist denunciation of the Puranas and the Sanatanists. They became something tantamount to the effeminate and the immoral in my mind. There was not much of traditional Sanatanism in my family due to the influence of Sri Garibdas, a saint in the nirguna tradition of Kabir and Nanak. Our women did keep some fasts, performed some rituals, and visited the temple and the Sivalinga.” (pp 4–5)

Despite the relatively recent use of the term ‘Sanātana’ to denote orthodoxy in the Indian context, this particular Sanskrit word has a clear connotation of ‘eternity’ in it. The sense of orthodoxy has come to attach itself to this word only in the wake of the rise of reformist sects such as Nanak Panth, Kabir Panth, or in more recent times, the Arya Samaj. It is a later phenomenon in the vast and continuing life of the Indic civilization; manifesting at a time when, in retrospect, the Sanātana ways were deemed relatively more rigorous and old-fashioned by the newly sprouted reformist sects.

Therefore trying to understand the meaning or essence of ‘Sanātana’ in such relativistic terms would result in a twofold error: the first of which is akin to trying to measure the depth and breadth of a grand river solely by studying its channels; and the second error is akin to evaluating the elements of a person’s character solely based on the reports and reactions of the critics of those elements.

To get a wholesome, undiluted sense of what Sanātana means, we must look for an emic perspective within the Sanātana fold; that is, our approach to Sanātana Dharma should be to study it in terms of its internal elements and their ways of functioning or interacting.

The most striking feature of the Sanātana worldview is its pragmatic approach to life, an approach that foregrounds death as the inevitable, inescapable truth of the human condition. The Sanatanist stream of the Indic Civilisation looks death squarely in the eye. It even celebrates death! At first encounter, it appears as a strange notion – this idea of celebrating something so despairingly final as death.

But upon closer examination, one begins to appreciate the utter necessity of such an attitude: it is only when one comes to terms with this inevitable truth that sooner or later he has to die, that one truly starts to evaluate the worth of his life in real terms.

It is for this reason that we find this inevitable truth being repeatedly highlighted through the texts, stories, and philosophical discourses that embody the Sanātana Dharma. It is a core theme of the Sanātana Dharma; for according to the Sanātanī-s, the realization of the smallness and futility of one’s material life is the point of departure towards one’s Life in Dharma. According to this view, one’s life truly begins only when death starts haunting his thoughts — until that point he had been living a life of delusion, a life of forgetfulness.

To feel restless at the thought of death lurking somewhere in the deep dark horizon lying ahead, to feel its presence like one feels the presence of an unseen tiger that one definitely knows is crouched right behind the bushes while passing through a jungle — to be unsettled by the thought of death, to the point that the thought stirs one up in his sleep, even keeps one awake at nights — that is the moment, the turning point in one’s life when he wakes from his deep slumber of a materialistic life to a real-life rooted in Dharma.

Thenceforward starts one’s enquiry to discover the secrets contained within the deepest lair of one’s Self, and one’s journey towards liberation. And so we find Yudhiṣṭhira in the Mahabharata replying to Yakṣa’s question as to ‘what is the most bizarre thing on earth’ in the following terms:

“Everyday living beings enter the abode of Yama [i.e. they die], and still the rest [of those who are alive] wish to live forever [i.e. they go on living in a manner as if their current status quo will be perpetual and death will never befall them]; what can be more bizarre than that?”

— 57, the chapter titled Āraṇeya, Vana Parva, Mahābhārata

The very opening statement of Īśvara Kṛṣṇa’s Sāṁkhya-Kārikā, a central text in the Sāṁkhya philosophy — the oldest of the six ‘orthodox’ Hindu philosophies — declares that:

“Because of the bludgeonings of the three kinds of duḥkha [i.e. suffering], an enquiry into the means of preventing [these three kinds of suffering] arises”. These three kinds of duḥkha are — ādhyātmika, ādhidaivika, and ādhibhautika duḥkha. When one looks at human suffering from this perspective, found in the Sanātana Hindu philosophy, one can no longer look upon suffering as evil or unwelcome — it then becomes the gateway to enter the Life in Dharma.

We see this exemplified in the life of a great son of India, whose first encounter with the three forms of human suffering — dotage, disease, and death — had awakened him to his real life and set him on the path of becoming ‘Buddha’ or the Enlightened One.

The Jātaka tales tell us that prior to that chance encounter with human suffering, Prince Siddhartha was living a life of dreams, of delusion; a life that was purposefully designed to keep out all forms of suffering from entering the prince’s consciousness. For it was prophesied that the Prince, who was destined to pursue the life of enquiry into the means to end suffering, would wake up from his artificially concocted dream-life the moment he encountered suffering in any form.

In a way, the epic life-story of the Buddha—the story of the unwitting Prince Siddhartha’s transformation through encountering duḥkha and his decision to set off on the nivṛtti mārga (i.e. the path of a transcendental realization of the true meaning of life) — is the archetypal story for every human being’s ultimate destiny.

It is not only the destiny of the Śākya Prince of yore to remain deluded by the many colors of life for some time and then finally wake up by encountering duḥkha, but of every person in the human form. This pattern, this journey of life, is beyond all differences of race, caste, or creed; it is beyond the separations in time and space—it is eternal, and thus it is a Sanātana phenomenon.

Up to the point when the human being encounters death squarely until he sees death’s significance for his life in its entirety and absorbs it in so as to be deluded never again by the ephemeral, he remains a veritable nāstika in the true Sanātana Hindu sense of the term—no matter how many pūjā-s he may perform, no matter how many offerings he may have made.

But as soon as that moment in his life presents itself before him, something in him changes fundamentally. In the words of the Upanishads, “śraddhāviveśa”—faith enters him, and he is no longer satisfied with the outer performance of life without having a firm grounding in the living spirit. This transformation is the gaining of the best form of faith—a faith which is not a blind belief; but rather a strong conviction in oneself, the conviction in the utterances of the śāstra-s, love of Dharma, and a burning zeal for the Truth. This is also known as āstikya buddhi.

References:

- Radhakrishnan, S. The Principal Upaniṣads. HarperCollins Publishers, Noida: 2014.

- Lokeshwarananda, Swami. Upanishad Vol. I. Ananda Publishers, Kolkata: 1999.