Abanindranath Tagore helped proliferate the idea of Indic values in art. His efforts went on to motivate millions of Indians to fight for Swaraj.

By Sreejit Datta, Assistant Professor, Director of Civilisational Studies Practice & Resident Mentor at Rashtram

Dr Abanindranath Tagore, CIE, a formidable thought leader in the emerging Indian nationalist art movement in Undivided Bengal, was born on this day in 1871 (which happened to be the Janmashtami tithi that year) at Kolkata’s Jorasanko residence of the legendary Tagore family. As yet another illustrious member born in the Tagore family, Abanindranath, popularly remembered by generations of Bengalis as ‘Aban Thakur’, grew up in the distinctive artistic atmosphere of Thakur Bari – the family home of the Tagores, in the company of other illustrious Tagores like grandfather Girindranath – a landscape artist following the European style, elder brother Gaganendranath – a pioneering modernist artist of India who developed a post-Cubist style, father Gunendranath, and uncles Jyotirindranath and Rabindranath. Both Gunendranath and Jyotirindranath were artists and early students of the Art School at Bowbazar which later became the Government School of Art, Calcutta

As a boy, Abanindranath made copious use of his father’s paint box and brushes to capture the rural landscape of Champadani on the river Ganges where he came to live with his father in the isolated garden house of the Tagores. His artistic faculty during this time was also stimulated by the eerie and the uncanny in nature that surrounded this rural home, like the jackals at night which devoured ducks by the garden pond and left the grounds strewn with their beautiful feathers and bones. The eerie flowed into grief and desolation as Abanindranath experienced the death of his father in this riverside home when he was only 10 years of age. The sketches and paintings by Aban Thakur of dilapidated temples, moonlit ruins, and melancholy river embankments, which often accompany his mellifluous prose, perhaps carry the impressions of this formative period.

In his youth, Abanindranth took lessons on cast drawing, foliage drawing, study, and pastel from Signor Gilhardi, an Italian artist, and attended the studio of Mr. Charles L. Palmer. However, by 1900, the artist’s stylistic orientation had shifted from European traditions of pastel works towards watercolour. This transformation came to completion when he went to Munger where he devoted days sitting on the river embankments painting in watercolour the India of the old. Soon after, Abanindranath began painting the famous series of “Krishna Lila” – a turn in his journey which marks his abandonment of European style and subjects for once and for all.

Thereafter, Abanindranath participated along with his elder brother Gaganendranath in the building of the “Indian Society of Oriental Art” in Calcutta; and later, inspired and mentored by Swami Vivekananda’s foremost disciple Sister Nivedita, Abanindranath spearheaded the Bengal School of Art movement which promulgated a distinct Indian modernism rooted in traditional Indic themes, motifs and styles in art, blossoming across the country during the era of British Raj of the early 20th century. This highly original artistic movement marked the synthesis of folk art, Indian painting traditions, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain imagery, indigenous materials, and motifs from contemporary rural life. The artists of the Bengal School brought a dynamic tenor to Indian identity, the idea of liberation, and freedom. Thus, from an ideological standpoint, the Bengal School conflated with Swadeshi – the movement of self-realisation and self-reliance in the face of the British colonial encroachment in thought, action, and territory.

In 1905 – at the height of the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal – Aban Thakur painted the iconic painting of the ‘Bharat Mata’, which would lend him immortality in the world of Indic art. The painting depicted a sadhvi clad in saffron robes, her four hands upholding sheaves of rice, a cloth of white, a japamala (beads for meditation), and a book. Her head is haloed and lotuses bloom at her feet. The luminous tinge of yellow at her feet and her head attracts the viewer to look at her feet and her crown first. She is the very embodiment of the Sanatana Indian consciousness.

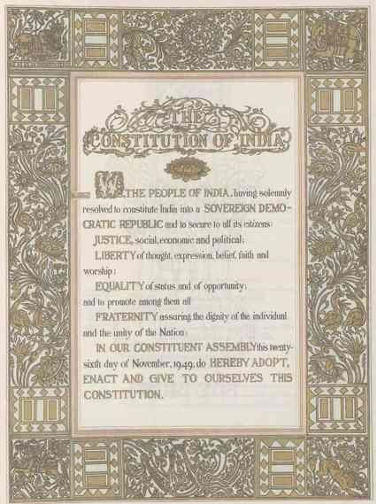

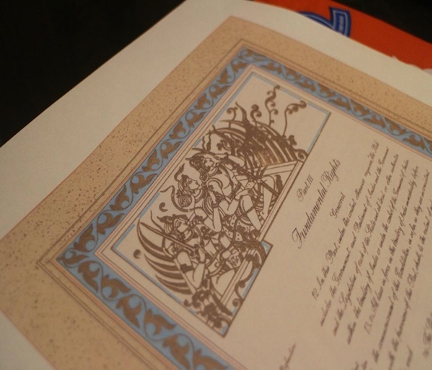

The received Jnana Shakti of the Tagore family, the induced Iccha Shakti of Sister Nivedita’s inspiration, and Abanindranath’s own inherently creative Kriya Shakti combined and manifested in the form of the Bengal School of Art, which was both an institution-generating force and an exceedingly successful indigenous artistic movement. It gave rise to a group of stalwarts in the field of art, such as Nandalal Basu, Mukul Dey, Sudhir Khastgir, Asit Kumar Haldar, Manishi Dey, Kalipada Ghoshal et al, most of whom were Abanindranath’s able disciples, and together they brought about a new awakening in India and revived Indian Art which lay in oblivion and decadence for centuries. Nandalal Basu, one of Abanindranath Tagore’s foremost disciples and his rightful successor in leading the Bengal School of Art movement (later largely centred in the Kala Bhavan, Visva Bharati, Shantiniketan), would go on to be commissioned to create the rare handcrafted first edition of the Constitution of India. The handcrafted limited edition copies were created by the meticulous craftsmanship of Nandalal and his disciples, and those copies still bear the legacy of Abanindranath Tagore’s reinvigoration of indigenous themes, motifs and artistic styles of the age-old and yet timeless Indic civilisation.

References:

Dey, Mukul. “Abanindranath Tagore: A Survey of the Master’s Life and WorkI”. Abanindra Number, The Visva-Bharati Quarterly, May – Oct. 1942.

Das, Shilpi. “How Nivedita’s Contribution to Indian Art History Shaped the National Movement”. Published in the heritagelab.in, November 4, 2019.