Riya, Faiz, and Ravi were sitting in their school canteen during lunch break when they noticed one of their teachers, Ms Biswas. Seated across the aisle, she was engrossed in a bright orange book with a simple title, Politics by Aristotle. They had been introduced to Aristotle recently in their social studies classes. So, they decided to approach her out of curiosity.

Riya: Good afternoon, ma’am. We observed that you were reading an interesting book.

Ms Biswas: Hello, Riya. Yes, I was looking at some quotes related to The Tragedy of The Commons.

Faiz: What’s that? Sounds like a theory or something.

Ms Biswas: Yes, Aristotle says, “That which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it.” What do you gather from that?

Riya: That we don’t care about the things we share…

Ms Biswas: Exactly. He believed that selfish exploitation of resources could threaten our livelihoods and societies at large.

Ravi: I see…do you mean natural resources, ma’am?

Ms Biswas: Yes, Ravi. Like trees, bonds, and the air we breathe.

Riya: But, Ms Biswas…

Ravi: Ma’am, I think this concept would be more apparent if you explained it to us with a story like you always do.

Riya: Yes, I always remember things that way, too!

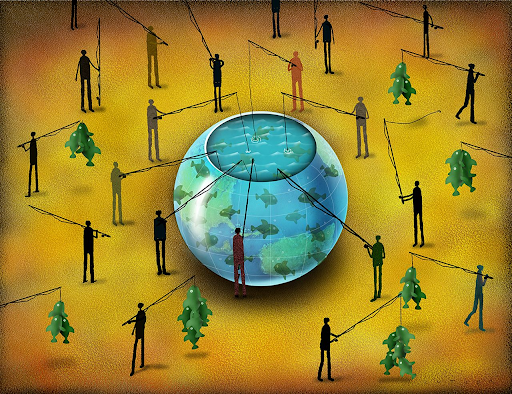

Ms Biswas: Okay, so consider a scenario with a small pond having 12 fish. Ignore things like the gender of the fish, but remember one point: The 12 fish consist of 6 different pairs that reproduce every night, giving birth to one fish each.

Now, imagine that four fishermen share the pond. If each fisher catches one fish and takes it home, the pond would have eight separate fish, or four pairs, left at night.

Riya: Each pair would reproduce one more fish by the next day.

Ms Biswas: Correct, and the pond would have four new fish.

Riya: It would have 12 fish once again!

Ravi: Wow, that was a fascinating math problem. But how does it relate to the Tragedy of the Commons?

Ms Biswas: This example shows that nature can still heal itself if everyone takes their assigned quota. But if the fishermen were greedy and took more than one fish home, the pond would eventually run out of its resources. Everyone in the community would starve – a tragedy.

Image courtesy of Dave Cutler

The bell rings, and the three friends return to their respective classes while Ms Biswas goes back to reading. But the discussion leaves the kids curious for more. They decide to meet over the weekend.

The following Sunday afternoon, they get together at Faiz’s house, delighted to know that everyone has already researched some articles and videos around the topic.

Riya pulls out a blog about something called ‘Circular Economy.’ She reads aloud:

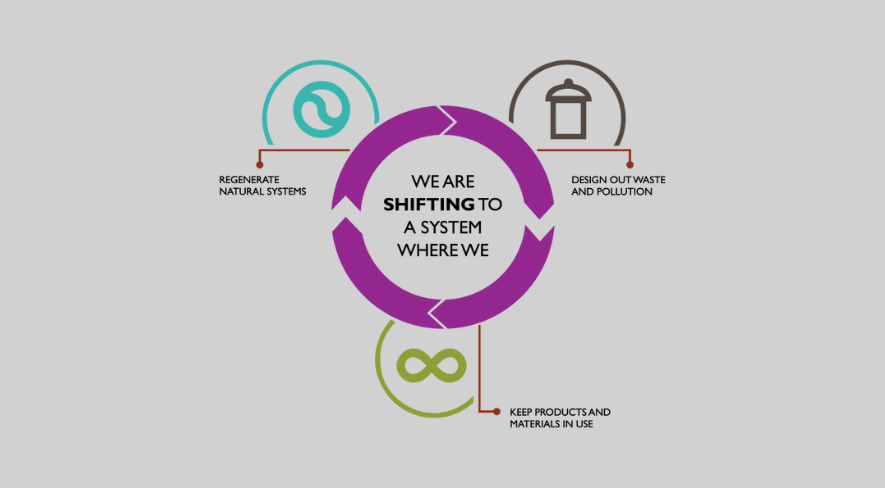

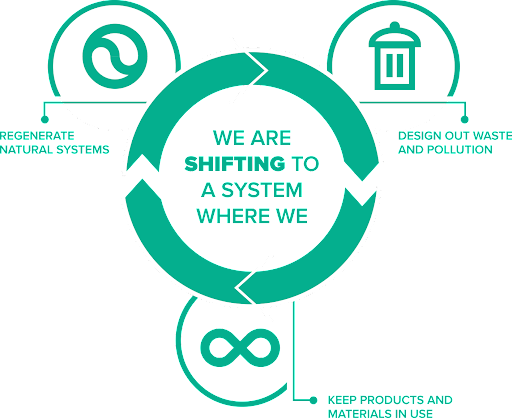

A circular economy is a systematic approach that rethinks how we make stuff. It explores how we can redesign our economy to create restorative processes. It means eliminating waste of resources by employing methods like reuse, repair, refurbishment, sharing, remanufacturing, recycling, etc. These practises, in turn, create a closed-loop system and minimise carbon emissions.

Image Courtesy of Ellen Macarthur Foundation

Then, Ravi jumps in to add that he also found similar things when he started browsing for ways to contribute. He had looked for videos of products imitating nature’s circular process. He shares ideas like candy wrappers made from mushroom roots, cars running on biofuels like ethanol, bike tracks and car parks made of printer cartridges, water-free and self-cleaning paints, secondhand shopping malls, and cafés making numerous products made from repurposed e-waste.

“This subject is too vast! But let’s not lose track,” interjects Faiz. Both of you are trying to say that we need to move away from the TAKE-MAKE-DISPOSE model. And everything should move in a flow, just like in the living world.

“Yes, everything from design, manufacturing, and transportation to our consumption and reuse,” Riya exclaims.

“That’s a brilliant backdrop for a futuristic sci-fi flick,” quips Ravi. It even reminds me of the classic disclaimer they put: No resources were lost in the process of making this.

“But let’s not lose track.”

[Sources: What is the tragedy of the commons? Lesson by Nicholas Amendolare, TED-Ed; The Circular Economy in Detail, Archive, Ellen Macarthur Foundation.]

Contributed by Arushi Sharma, this concept note got featured in the Sustainability edition of The Plus magazine.