A widely influential yet unknown revolutionary, Kanailal Dutta accomplished some heroic acts within a short lifespan of just twenty years, and even made the ultimate sacrifice for the cause of his motherland.

By Sreejit Datta, Assistant Professor, Director of Civilisational Studies Practice & Resident Mentor at Rashtram.

Yesterday, 30th of August, marked the birth anniversary of a man who should have been worshipped and hailed as a liberator and a great son of Mother India in every corner of this free country. And yet, there was hardly any celebration commemorating his valour, his heroic acts accomplished within a short lifespan of just twenty years, and his ultimate sacrifice for the cause of his motherland. Adding insult to injury, he has been designated as an ‘extremist militant’ at best, and a ‘terrorist’ at worst in the ‘official’ accounts of the Indian freedom struggle’s history. Perhaps this is how an ideal Karma Yogi’s legacy is meant to look like: the effects of his intense life working unseen and silently through the ages; a life which was utterly sacrificed for the comfort and freedom of others, while the life itself stays unsung and buried deep in some unexplored, dusty archive – even attracting ignominy from the very people for whose sake it was smilingly given up.

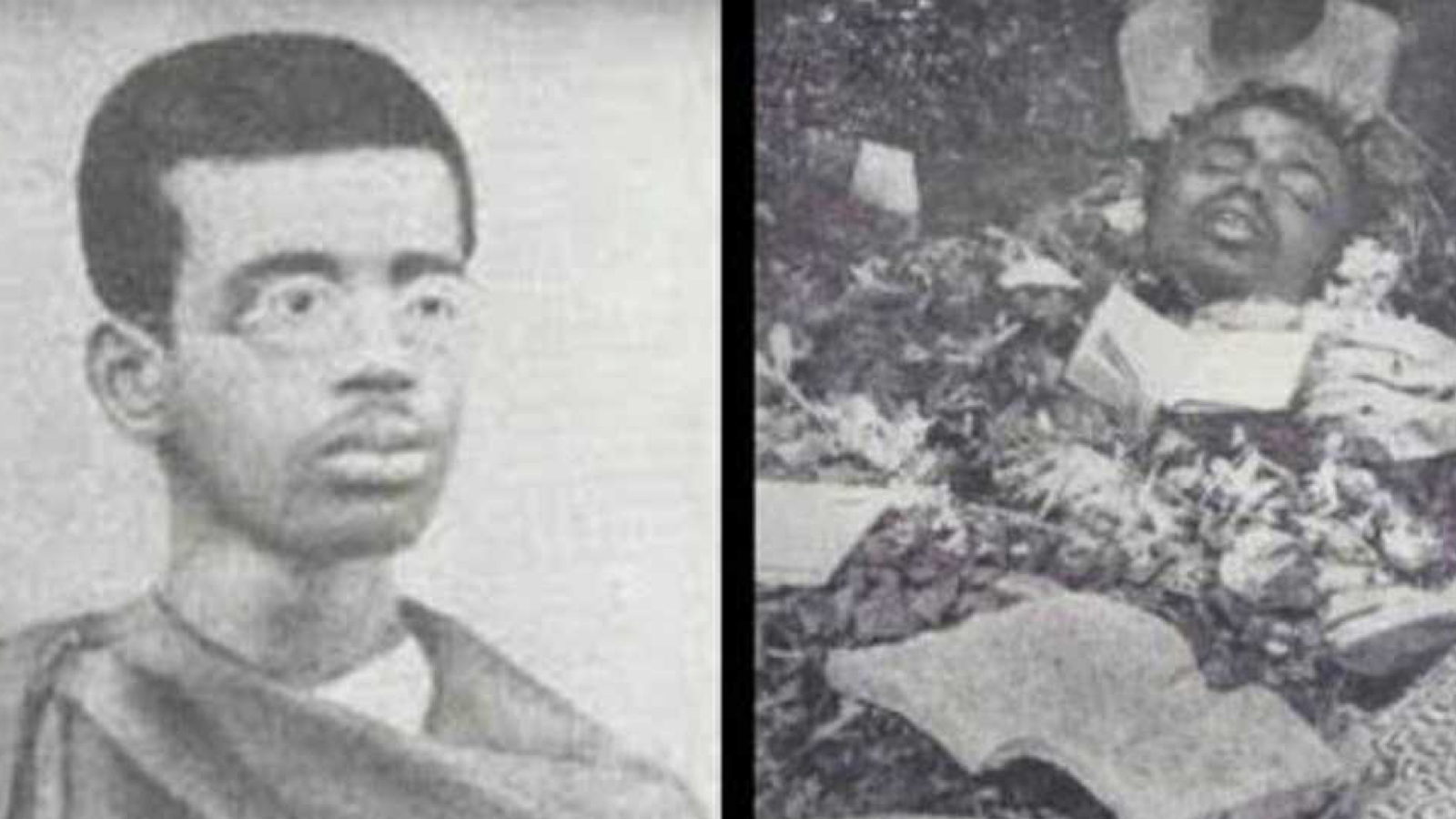

Although the lives of many a great son and daughter of Mother India fit the above description, in this specific instance we are talking about Sri Kanailal Dutta, a revolutionary freedom fighter born in Chandan Nagar of today’s Indian state of West Bengal, who was arrested by the British Police in connection with the Muzaffarpur bomb attack in 1908; and who was convicted a few months later, along with his comrade Sri Satyendranath Bose, for the murder of Naren Gossain, a revolutionary-turned-approver for the British colonial administration.

The date on the British-instituted Gregorian calendar was November 10, 1908. Early in the morning on that day, Kanailal Dutta had been executed by hanging till death inside the Alipore Jail in Kolkata. When the mortal remains of Kanailal were brought outside and the bier started to move towards the Keoratolla Maha-Shmashan, situated on the banks of the Adi Ganga at Kalighat for cremation, thousands gathered and jostled with each other to get to the bier – for, it is considered a sacred duty of the Hindu man to carry the bier of a deceased relation on his own shoulders. For those men, women, and children, whose numbers kept increasing by leaps and bounds as the bier headed towards the cremation ghat, Kanailal had overnight become one of their own! All were shouting “Jai Kanai! Jai Kanai!” (Hail Kanai! Victory to Kanai!) Flowers poured in from the balconies of the households that lay by the streets through which the procession passed. The body was decked with garlands and floral offerings from the crowd. Much to their embarrassment, the British police witnessed an extraordinary event that day, the like of which they had never seen anywhere before, and they took a lesson from it. Within two weeks, co-accused Satyendranath Bose’s execution was carried out, and his body never came out of the Alipore Jail.

As the procession bearing Kanailal’s mortal remains inched closer to the Keoratolla crematory, the size of the crowd grew to lakhs. And there lay on the bier, now being carried over the shoulders of hundreds, the body of Kanailal wearing the satisfied face of the victor.

Fifteen years down the line, a Bengali booklet on Kanailal was published by Motilal Roy – another comrade of Kanailal – in which we get a glimpse of the scene when the bier reached its destination and Kanailal’s body was put on the funeral pyre:

“As soon as the blanket was carefully removed, what did we see – language is wanting to describe the lovely beauty of the ascetic Kanai – his long hair fell in a mass on his broad forehead, the half-closed eyes were still drowsy as though from a test of nectar, the living lines of resolution were manifest in the firmly closed lips, the hands reaching to the knees were closed in fists. It was wonderful! Nowhere on Kanai’s limbs did we find any ugly wrinkle showing the pain of death…”

This booklet, originally published from Chandan Nagar, then a French Colony, was immediately banned by the British government under the Sea Customs Act of 1878, which prohibited any “objectionable materials” from being transported into British territories. Even fifteen years after the death of this formidable Bengali Warrior of the Indian freedom struggle, the mighty British Empire feared a mere mention of Kanailal’s final rites!

Had Kanailal and Satyendranath not killed the approver Naren Gossain, perhaps Sri Aurobindo Ghosh (later Sri Aurobindo) would never have come out of the British prison. But for Kanailal’s final bullet which pierced the chest of Gossain and caused his death, it is very likely that Sri Aurobindo would have ended up spending the rest of his days incarcerated in Andaman.

The Muzaffarpur bomb attack in 1908, intended to kill the racist and notoriously cruel British judge Douglas Kingsford, resulted in the execution of the legendary freedom fighter Khudiram Bose by the British colonial administration. In the wake of this incident, the colonial administration ramped up searches and raids across Bengal and Bihar. It was at that time when Kanailal was arrested by the British police, along with at least forty other nationalist warriors, who were detained in Kolkata’s Alipore Jail for trial. A man named Narendranath Gossain, also arrested at that time, turned approver and became the crown-witness. Gossain started taking names, and many more arrests followed. Most of these men were associated with the nationalist organisation Anushilan Samiti and the Bengali paper Yugantar, started by Sri Aurobindo Ghosh, which paper was a prominent platform for the nationalists. Sri Aurobindo’s younger sibling Barindra Ghosh, a key leader of the nationalists, was also arrested. In fact, Gossain’s revelations to the British police were instrumental in compromising a dozen nationalist warriors, including Sri Aurobindo. Thus started the historic state trial which is known by the name of ‘Alipore Bomb Case’. All the arrested nationalist warriors, including Sri Aurobindo, were charged with waging war against the British Emperor.

On the pretext of making more revelatory statements to Gossain, both Satyendranath and Kanailal met the approver in the prison hospital. Both of them opened fire at Naren Gossain inside one of the wards of the hospital, but Gossain managed to escape to the gates. Kanailal took a daring step and chased him down, shot him through the chest from a revolver which was smuggled into the prison in one of the boldest adventurous feats of revolutionary freedom movements in the history of the entire British Empire. Kanailal’s firing caused Gossain’s death. If it were not for Kanailal’s audacious act, we would perhaps never have seen Sri Aurobindo walking out of the British prisons. Gossain would have caused immense damage to the freedom movement, which is why Kanailal in his statement to the DM said:

“I wish to state that I did kill him. I do not wish to give any statement why I killed him. Wait, I do wish to give a reason. It was because he was a traitor to his country.”

News of Naren Gosai’s assassination caused great celebrations in Bengal. Surendranath Banerjee distributed sweets in the office of the Bengalee newspaper. People danced in the streets (source – Matilal Roy’s booklet). Youngsters even performed Puja of Kanailal & Satyendranath’s murtis. When the question of an appeal came up, Kanailal simply said, “There shall be no appeal”. Commenting on this, renowned chemist and a great sympathiser of the brave young freedom fighters, Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy remarked that Kanai taught the Bengalis the proper use of ‘shall’ & ‘will’, pointing to Kanailal’s precise application of the word ‘shall’ in the imperative.

Kanailal’s mentor Professor Charu Chandra Roy, who initiated him into the nationalist mantra, has left us an account of one of the wardens at Alipore Jail of the time in his memoirs. A day before Kanailal’s hanging, the British jail warden found Kanailal with a smiling face, and retorted that all his smiles would be wiped out the next day when he would be taken to the gallows. Next morning on the gallows, Kanailal smiled at the warden and asked, “How do you find me now?” No words escaped the warden’s lips at that time. The warden had later confessed to Charu Chandra Roy, “I am the sinner who has executed Kanailal. If you have a hundred men like him, your aim will be fulfilled.”

On the blessed day when Kanailal’s mortal remains merged into the holy flames of the funeral pyre at Kalighat’s Keoratolla, a great rush was observed among the lakhs of people in the crowd to collect a little amount of the ashes from the pyre of Kanailal. In this connection, Mr F.C. Daley, a high-ranking British police official, had remarked: “The stuff which was sold in the name of Kanailal Dutta’s ashes was apparently fifty times the real amount of the ashes found at the crematorium!”

These ashes were truly sacred for millions of men and women of Kolkata, who had all gathered on that day before the gates of the Alipore Jail to carry one of their great warriors on a procession of victory through the city. These ashes, for them, were a holy memento, prized above most other dear possessions, from the sacred fire of the ‘Agniyuga’ (‘Fiery Age’) of the Indian Nationalist Movement in Undivided Bengal, which burned bright for decades to come – and which fuelled the likes of Bagha Jatin, Rash Behari Bose, Master Da Surya Sen and his band of nationalist warriors at Chattagram, and ultimately, the great maverick leader Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, who crossed continents to raise an army and wage a decisive war against the British Empire, dealing its Indian colonial project a mortal blow.

References:

“Alipore Bomb Case” available online at http://www.sriaurobindoinstitute.org/saioc/Sri_Aurobindo/alipore_bomb_case

“Chitabhasma Kinte Hurohuri” available online at https://www.anandabazar.com/events/independence-day/independence-day-special-huge-crowd-brought-ash-of-martyr-kanailal-dutta-after-his-cremation-1.1031848

Ghosh, Durba (2017), Gentlemanly Terrorist: Political Violence and the Colonial State in India, 1919-1947, Cambridge University Press

Sen, Shailendra Nath (2012), Chandernagore: From Bondage to Freedom 1900-1955, Primus Books